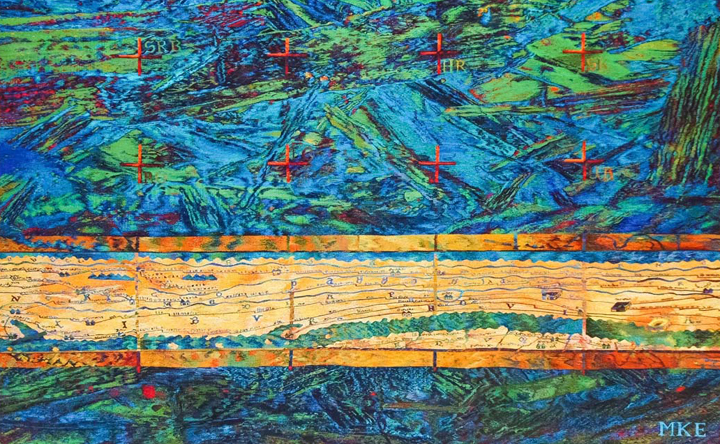

Made in: 1995-1996

Owned by the Budapest Museum of Applied Arts: Haute-lisse, 330x350 cm

Tapestry at the Turn of the Millennium in a Europe Without Borders.

Edit Balogh, Ágnes Bálint, Judit Baranyi, Hajnal Baráth, Noémi Benedek, Eszter Bényi , Emese Csókás, Ildikó Dobrányi , Eta Erdélyi, Júlia Erdős , Márta Faragó , Éva Farkas , Ilona R. Fürtös, Beatrix Gremsperger, Zsófia Harmati, Ritta Hager, Beáta Hauser , Hajnal Ipacs, Ágoston John, Edit Kapros-Kósa, Erzsébet Katona Szabó, Ágnes Kecskés, Imre Kovács , Péter Kovács, Krisztina Kókay, Anna Mária Kőszegi , Ida Lencsés, Edit Lugossy, Katalin Martos, Irén Málik, Indira Máder, Erzsébet Mészáros, Katalin Nagy, Éva Nyerges, Eleonóra Pasqualetti, Rózsa Polgár, Richard Rapaich, Flóra Remsey, Éva Richter, Éva Rónai, Gizella Solti, Nóra Tápai, Mária Vajda, Bernadett Varga, Ágnes Vastag, Katalin Zelenák

Tapestry without borders – The work entitled ‘Tapestry without borders’ woven in 1996 is not only a noble offering created for the millecentenarian celebrations, a bow to the 1100 year long Hungarian presence in the Carpathian basin, but it is also the common millenary message of a handful of tapestry weaving artists in a Europe ‘without borders’ .

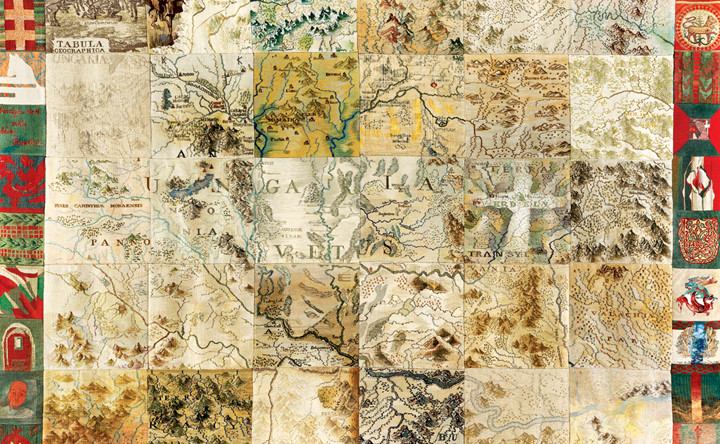

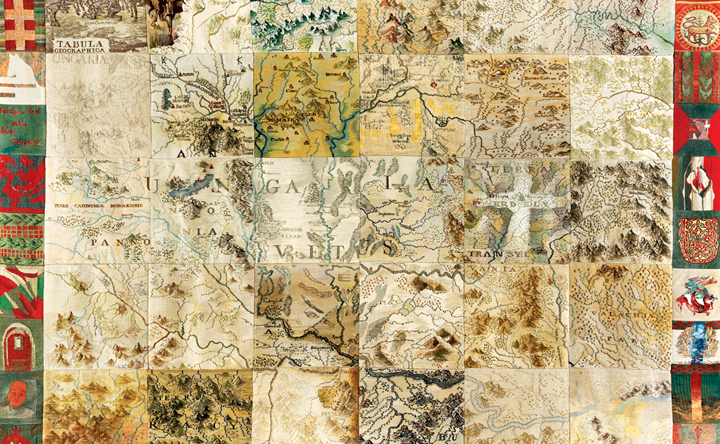

The impressively sized (300 by 350 cm) end of the millenium inspired gobelinmap is of symbolic significance and generates numerous thoughts. At the turn of the millenium the genre of tapestry looks back on a past of several centuries, adjusting either to the traditions of tapestry weaving or, through its own metamorphosis, to the cutting edge art trends. It is exemplary that it is permanently present in Hungarian art and more often than not it enables the collaborative realization of a common idea. This holds true in the case of the tapestry entitled “Tapestry without borders”, sewn together from 30 separate squares and 48 moulding squares surrounding it, the common work of 46 tapestry artists, the mark of their particular way of thinking collectively.

The English patchwork technique should be mentioned here, with numerous beautiful samples exhibited in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Common gobelin – The working title in itself refers to the fact that it was woven by several artists. When sewing together the inner part (30 squares – 30 different artists), the exact splicing of colours, hues, letters and words proved to be impossible.

Due to the various hands, ideas and the diversity in the quality and colour of the woollen thread used, a variation in hue, size or proportion of the squares, as well as shifts in the rivers and writing are fairly frequent. These apparent irregularities make the work vibrantly exciting and at the same time produce a unique harmony, a calm and unified view. Collective anonymity – The group harmonization of individual ideas, work methods and weaving techniques also has a gesture value from another point of view. By assuming collective anonymity, these artists considered community interests a priority.

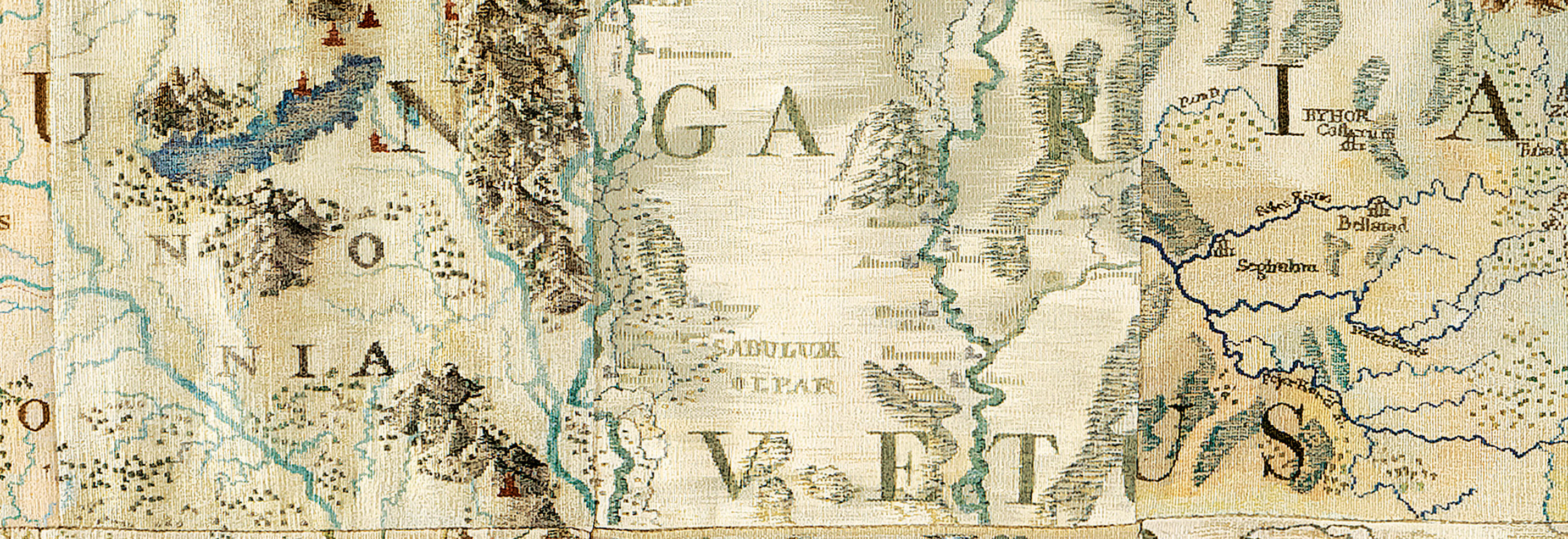

Hell Miksa’s map. Europe’s geographical centre – The forty six artists worked with the codices copiers’ humility and idiosyncracity on the basis of the Jesuit monk, Hell Miksa’s, map. He was an imperial and royal astronomer in addition to the designer of the observatory in Buda. He edited and drew his map which represents the Carpathian basin at the time of the Settlement of the Magyars in Hungary, in 1772. The work executed with scientific meticulosity was engraved in copper so that it could be multiplied. The tapestry artists and weavers reproduced the turn of the millenium gobelin variety of the punctilious map from the 18th century. After having enlarged and taken apart the original copperplate, they first wove the fragments, then later sewed them together.

Thus “ an achievement”, a message, a contribution was generated, which is an offering, a signalling and at the same time an imprint. We can be witnesses to a special continuity through the centuries. The new work takes its place in a linear continuum. The original drawing from the end of the 1700s is followed by a copperplate, which in its turn is followed by a modern duplicate leading to this new spectacle prepared with disciplined weaving at the end of the 1900s. The depiction of the Carpathian basin may well have other explanations. Many maintain that Europe’s geographical centre is in Hungary. This 20th century assumption is further nuanced by politician and worldwide famous geographer, Count Pál Teleki’s remark.

‘ The country lying in the embrace, the three quarter arc of the 1500 km long Carpathian mountain range is an outstanding geographical and political unit, an isolated territory, unique in the world.’ The map part of the gobelin – Similarly to the original map and the copperplate, the weavers adhered to the period’s hydrogeological map of the Danube’s catchment area. The artists drew the settlements, bridges and fords with woollen threads and marked the forests with a tree shape on the elements (each 50 by 50 cm) of the middle part of the tapestry. They used points for the presumable roads and stripping to indicate the probable moorlands.

The typical feature of old maps, the figurative scene or drawing in the topmost left hand square, can also be found here. Above the writing the Hungarian chieftains are lined up on both prancing and calm horses etching-like, following the original map drawing of raising Árpád onto his shield. The geographic landscape of the Komárom region is densely laced with rivers, so, because of the rich waterland, the tapestry is more colourful and better defined than the snowy upper squares. The middle part is more homogenous in its choice of colours.

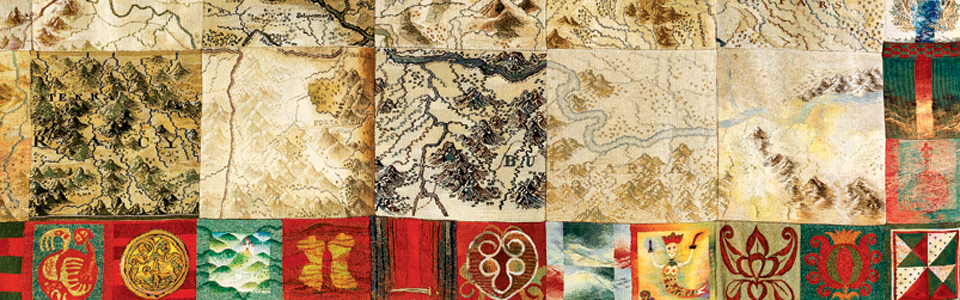

A bit lower the eye is attracted again by a few more brownish, greenish and greyish squares of tapestry or a quite light patch flashes vibrantly. The jumping letters of the word ‘Pannónia’, the shifts in the words, the various colours of the word Transylvania, the broken up line of the Danube, the cut-off waterways, the cross of Transylvania, the forest brown hills, the mountains indicated by small, dark green trees and the square split by the branch of a river are all surprising. The scenery shown from above, the mountains, rivers, lakes and settlements, fortresses and towns with their names are expressive and fire the imagination.

The Danube is worth noting, flowing across the whole woven map, which is still considered ‘a spiritual lead, a pulsating vein on Europe’s anatomical map’. The main river, which was and still is a famous cultural factor ‘links countries and nations as well as thoughts and ideas’. The Danube ( the longest river in Europe, part of the trans-European waterway) undergoes a specific metamorphosis in the different parts. It starts dominantly because of its wildest and most untameable stretch. This is followed by a less powerful band. It doesn’t even splice smoothly in the midsection. In the lower segment, the very dark and deep coloured passage is followed by a paling parallel stripe showing only the mere contour of the river. In the last square, it flows into the sea quite faintly.

These refined colour schemes confer particular beauty to the tapestry. The mould – Deep red and dark green dominates the more strongly coloured framing band (48 woven squares). These threads had been dyed previously to ensure uniformity as besides white, these two colours are those of the Hungarian flag. The enclosing is conveyed by the identical motifs in the four corner squares of the mould. Beside the reds and greens of the 48 squares (each 25 by 25 cm) gold, copper gold, stone white, greyish white, sky blue and mourning black are also interwoven in their strongest hues. A delightful series of images lines the squares, repetitively like a set of pearls, throbbing as a decorative band.

The woven images are interlaced with silhouettes, crosses, signs, symbols, seals, old banknotes, fragments, panoramas, coats of arms, heads, coins, texts, parchments, ancient purse decorations, scenes, archaeological findings and other historical memorabilia. Furthermore, animal figures, dreamlike appearances, pieces of flags, whisps of clouds, riders, horses, writings, monograms, swords, pillars, floral motifs, calligraphies, crowns, orbs and other motifs, hardly detectable or clear, intermingle.

The exact, unambiguous motifs conveying important meanings alternate with interesting, more abstract, more ambiguous, less obvious, expressive, subjective imagery in a subtle arrangement. Woven fresco – The splicing and harmonisation of the seventy eight squares is ensured by both the right choice (the map) and the meticulous gobelin technique. The latter guarantees the unity and uniformity between the work of different hands on account of the specific professional limitations as well as that of the given framework.

As an image, the tapestry is comparable to coffer ceilings or mosaic walls and conveys both unity and harmony. This large-sized goblin, a suggestive and colourful wall decoration is a worthy transmitter of a collective ‘offering, signalling and imprint.’ The language of the textile expresses the European end of the millennium attitude of a common will and of the ability to create something together in spite of diversity.

Ildikó Kontsek